Friction is the force that resists motion when two surfaces are in contact. In mechanical systems using bearings, controlling and minimising friction is essential for smooth, efficient, and long‐lasting operation. Plain bearings (also called sleeve bearings or bushes) rely on sliding contact rather than rolling elements, making them particularly sensitive to friction characteristics.

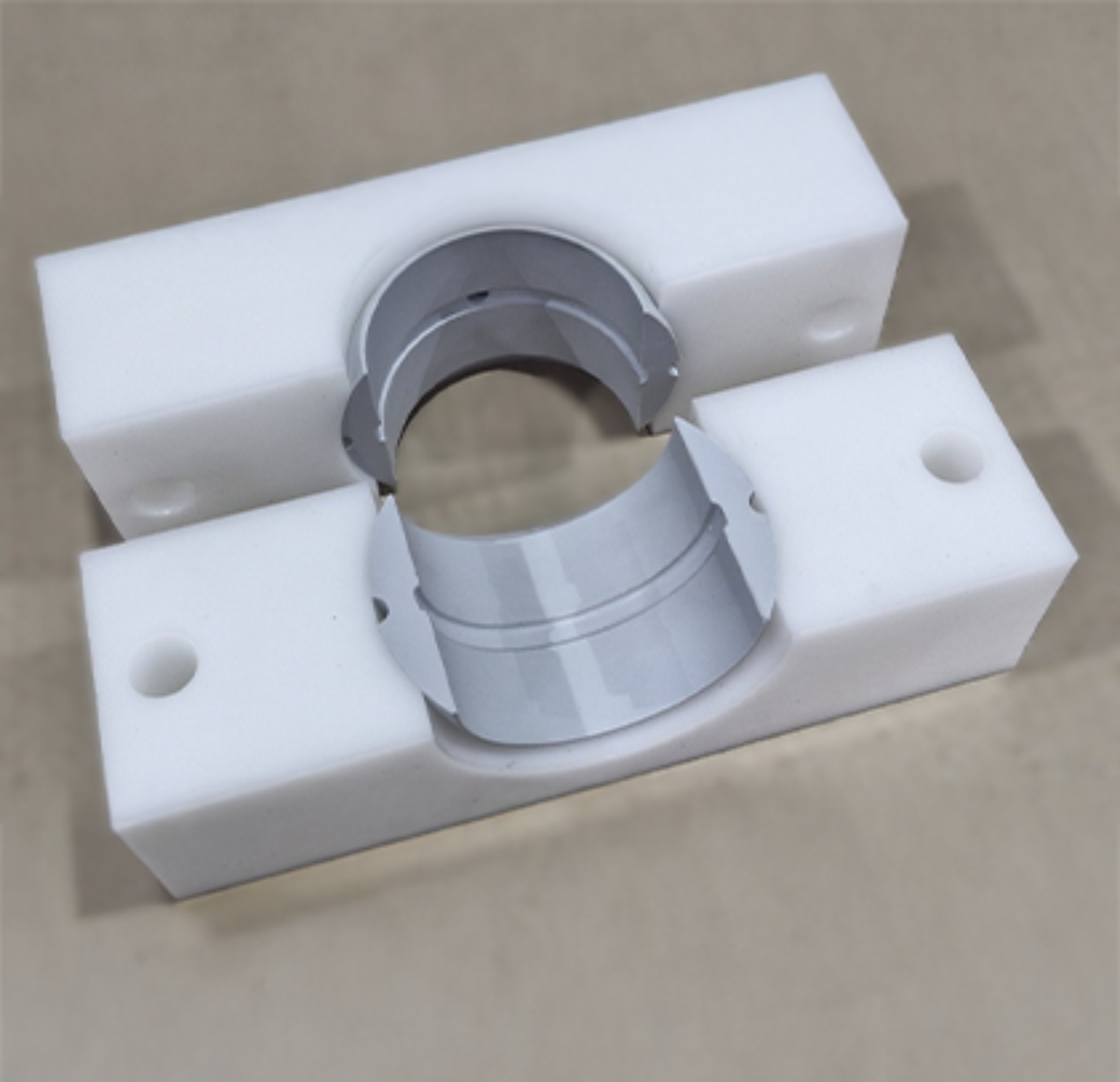

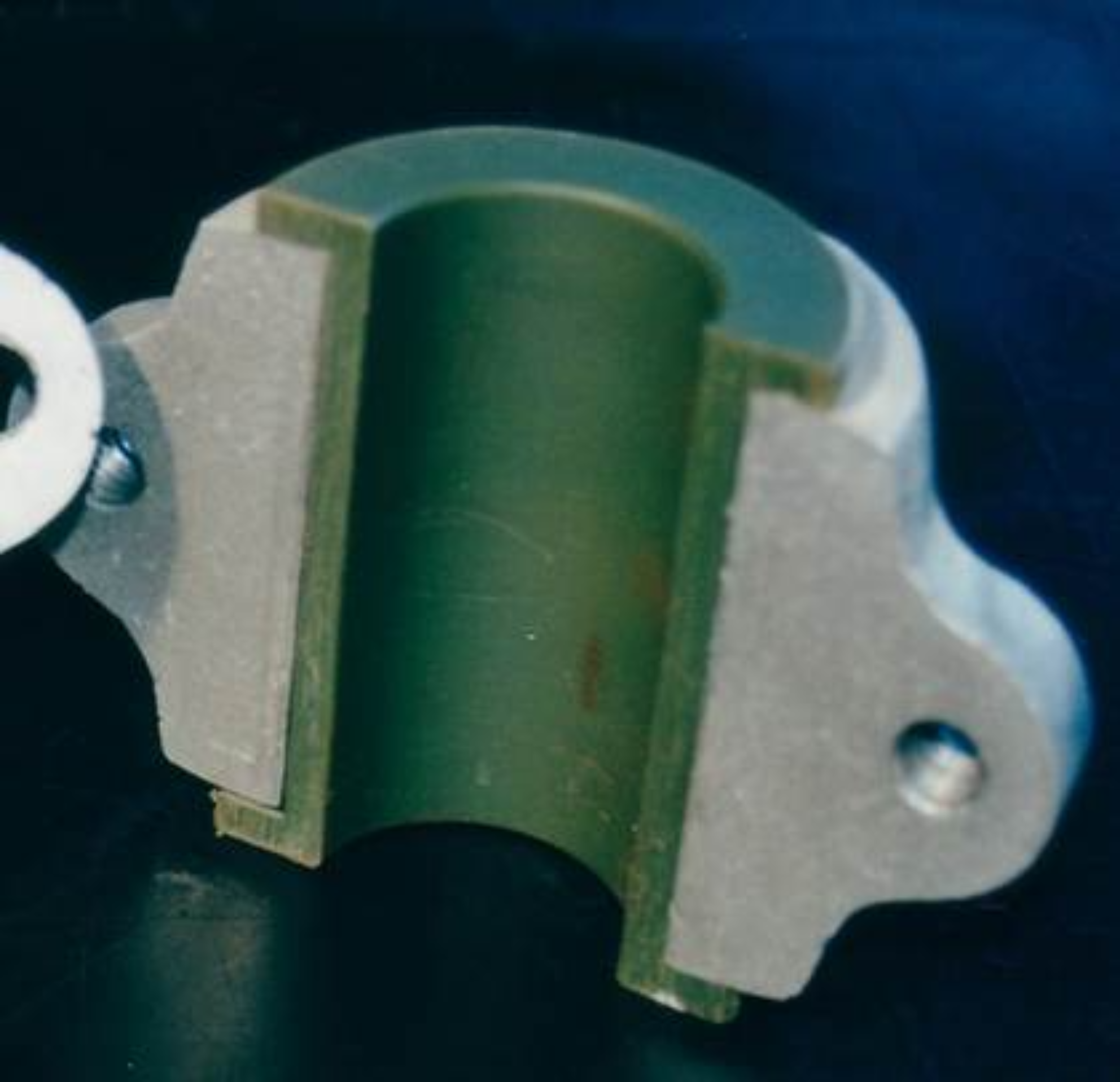

Plain bearings — including plastic plain bearings or plastic bushes — provide a low-friction interface on a shaft (or pin). Unlike ball or roller bearings, plain bearings do not contain moving rolling elements. Instead, the shaft slides or rotates directly against the bearing surface.

Because of the larger surface contact and sliding motion, plain bearings generate more surface friction and heat than rolling bearings. This makes the choice of material, surface finish, and counter-face material especially important to ensure efficient and durable operation.

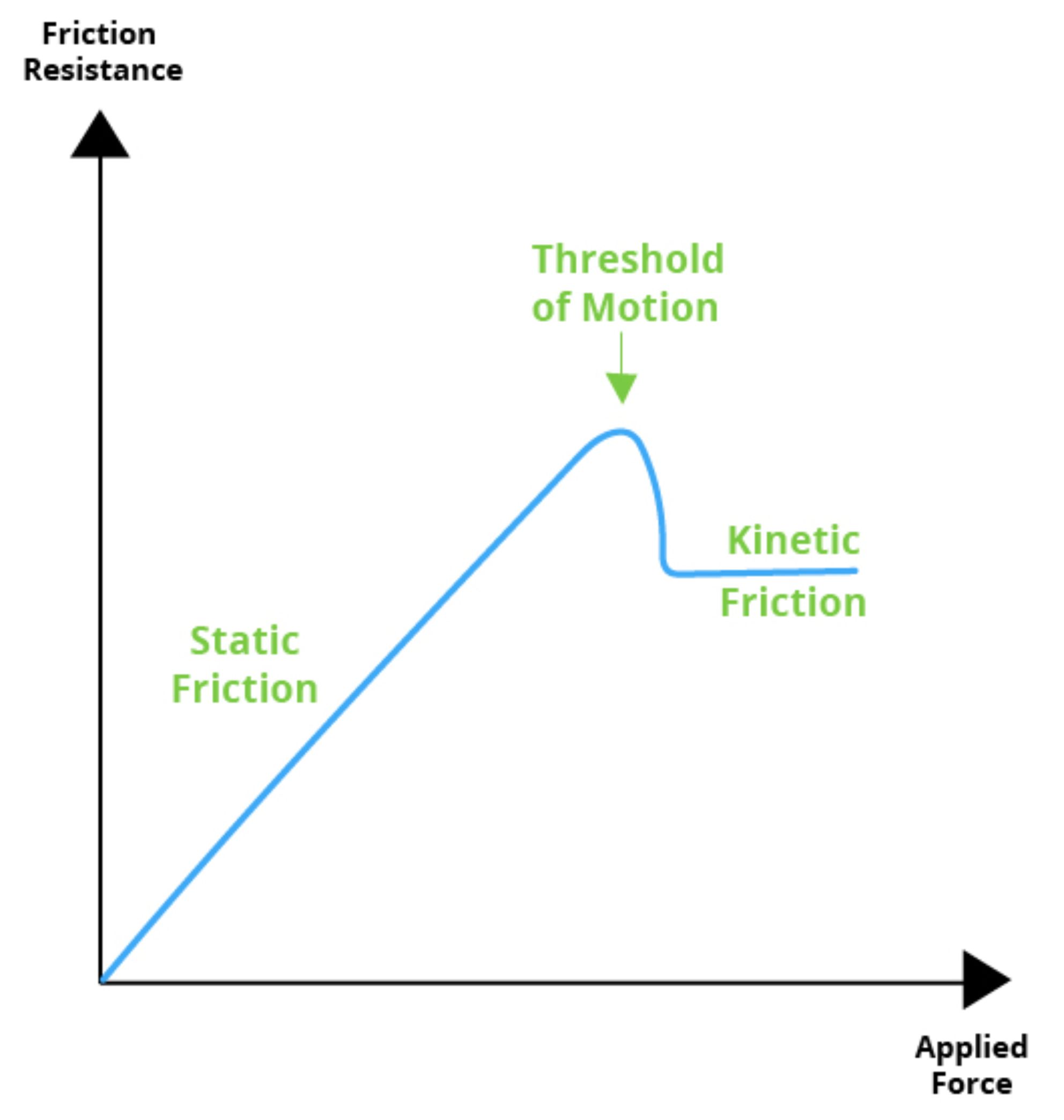

Static vs. Kinetic Friction — Why They Differ

When two surfaces are in contact, friction manifests differently depending on whether the surfaces are stationary relative to each other or in motion. In a plain bearing scenario, this distinction is crucial for understanding starting torque, wear, and movement characteristics.

Static friction (also called “stiction”) is the resistance to the initiation of motion when the shaft (or component) is at rest inside the bearing. The maximum static friction force that must be overcome to begin motion is given by

Fmax = µs X Fn

Kinetic (or dynamic) friction is the resistance once motion is ongoing — i.e., the force opposing motion while the shaft is sliding or rotating inside the bearing. The kinetic friction force is;

Fk = µk X Fn

where the kinetic COF is typically lower than the static COF, because maintaining motion generally requires less force than overcoming static contact.

In practice, this means it often takes more force (torque) to start moving a shaft inside a plain bearing than to keep it moving once started. This difference can also lead to phenomena such as stick-slip, where motion starts and stops irregularly, sometimes producing noise or jerky movement — especially if the difference between static and kinetic friction is large.

Plain Plastic Bearings and Bushes — Special Considerations

Plastic plain bearings (or plastic bushes) deserve special mention because of their growing use in many machines due to their favourable combination of low friction, self-lubrication, and excellent wear resistance (low maintenance).

Many plastic bearings are self-lubricating: manufactured from polymers imbued with lubricants so that they do not require external grease or oil. This reduces maintenance and avoids lubricant leaks, which is often desirable in applications where cleanliness or contamination prevention is important.

The coefficient of friction (COF) for such plastic bearings depends heavily on the polymer utilised and surface conditions. When self-lubricating, the COF can remain relatively low — but factors like shaft surface finish, load, speed, temperature and environmental contaminants influence real-world performance.

Because plastic bushes operate via sliding contact (not rolling), they often generate more heat than rolling element bearings for the same load and speed — meaning the material choice and design must account for temperature, wear rate, and clearance changes over time.

In short: plastic plain bearings may reduce maintenance and perform well — but only if the material selected and design (running clearances, press-fits, etc) are well matched.

Role of Lubricants — Reducing Friction & Wear

Lubrication can reduce friction, increase wear and provide efficient motion in plain bearings. The lubricant serves to separate the two surfaces (bearing and shaft), reduce direct asperity contact, and minimise heat and wear.

There are different lubrication regimes, each with different friction characteristics:

Boundary lubrication — where the fluid film is extremely thin or absent, and friction is dominated by solid-to-solid contact (or contact mediated by a thin film of absorbed oil molecules). In this regime, friction is significantly higher — and the characteristics of the bearing material (or embedded solid lubricant) become key.